What did The World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business rankings mean to a developing country citizen?

The fall of The World Bank’s EODB rankings has been quite spectacular. For an excellent round-up of the investigation into the EODB rankings, read Adam Tooze and Justin Sandefur. Both conclude – rightly, in my opinion – that junking the rankings is simply not enough. Heads should roll.

I am going to talk about something else here. In India, we knew something was up as soon as soon as the rankings started making an inordinate amount of news in the national media. And this happened primarily because Government of India (GoI) under PM Narendra Modi saw an opportunity to burnish India’s credentials as an investment destination by focusing on improving the country’s rankings.

A Government of India website reports:

Among the chosen 190 countries2, India ranked 63rd in Doing Business 2020: World Bank Report. In 2014, the Government of India launched an ambitious program of regulatory reforms aimed at making it easier to do business in India. The program represents a great deal of effort to create a more business-friendly environment. India as one of the top 10 improvers, for the 3rd time in a row, with an improvement of 67 ranks in 3 years.

India has emerged as one of the most attractive destinations not only for investments but also for doing business. India jumps 79 positions from 142nd (2014) to 63rd (2019) in 'World Bank's Ease of Doing Business Ranking 2020'.

The fortunes of the EODB in India mirrored closely the fame of Amitabh Kant, PM Modi’s blue-eyed bureaucrat who has a knack for schemes that create a big splash. It is a different matter altogether that many of these central government schemes are all glamour and no substance - ‘Make in India’, ‘Start Up India come to mind, and the ‘Aspirational Districts’ scheme seems another meaningless fanfare in the making.

The external investigations carried out on the World Bank did not identify India as a country where the EODB rankings were manipulated. The report only claimed evidence in the cases of China and Saudi Arabia. India is absolutely a country that still has a multitude of obstructive laws that make running businesses a nightmare. But India was also a country where one saw the perverse incentives that EODB generates, played out.

Form over substance: Governments love good publicity. Under PM Modi, GoI is obsessed with it, and has exerted itself tremendously to transform the farthest reaches of the government machinery (bureaucracy) to a publicity-generating instrument. Let’s take investments and capacity utilisation as a handy example.

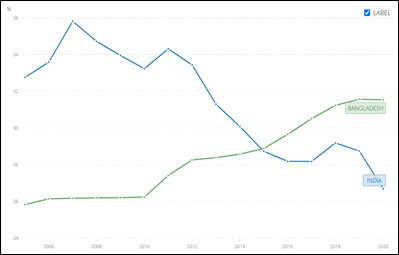

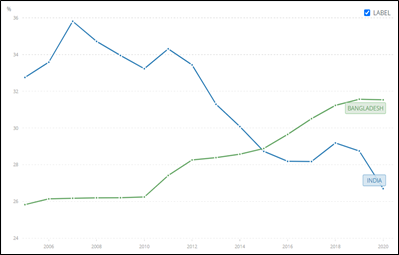

While the EODB rankings show that India’s rank improved tremendously between 2014 and 2020, this, below, is what The World Bank’s data on Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) comparing India and Bangladesh looks like. GFCF, which refers to aggregate investment in India as a percentage of GDP has been on an interminable downward trend. Investment is a key determinant of growth, and it is interesting to see Bangladesh faring better than India, and the trend suggests that the gap might widen in the years to come.

Now the Department for Promotion of Industry & Internal Trade Production (DPIITP) can argue that GFCF is an indicator that tells us about ‘fixed capacity’ and not capacity utilisation, and that our first priority should be improving the efficiency of utilisation of existing productive capacity. That is a fair point, but let’s look at what the data says:

So not only has India not improved the rate at which existing capacity is utilised, it has also not registered an increase in the percentage of GDP going towards fresh (greenfield) investments. India’s ‘Make in India’ scheme has simply not delivered. Reasons are manifold, but prominent among them are that they were undertaken by a government that had increasingly centrist tendencies and was usually too busy pursuing a bruising social and religious agenda.

This is not an isolated example. While India clocked its impressive rise in the EODB rankings, the rest of the economy had started languishing. In an article for The Hindu, Santosh Mehrotra and Jajati Keshari Parida estimate that the poverty headcount in India has increased by nearly 9 crore from 2011-12 to 2019-20, a stunning reversal of independent India’s steady poverty alleviation record. The stellar improvements in India’s EODB rankings have little to do with ‘ease of living’ that seems to be coming up as an occasional buzzword in government circles. PM Modi and his fanbase may have dreams of a country that looks like Singapore. However, the reality is that even in 2011-12, India had 27 crore people living below the poverty line, and crores more who were one catastrophe away from slipping below the poverty line.

Sadly, GoI had a choice to make in how it would utilise its limited bureaucratic capacity, and it chose to focus on global rankings, rather than real pro-poor policy. Given how the EODB rankings are publicised every year, The World Bank can hardly escape the charge that it set countries down a path of competition over something that amounted to very little in terms of real lives and livelihoods. Indeed, remember that a colossal blunder of the magnitude of Demonetisation, where 86% of India's currency notes in circulation were declared invalid overnight, seems to have had no effect on the ease of doing business in India. Indians must really wonder what the EODB rankings really capture!

Much of Indian media’s reaction to the rapid rise in India’s ranking was on sadly predictable lines. This helped PM Modi use the EODB to make claims about the success of his government’s economic reforms agenda in his re-election campaign in 2019.

World Bank data also tells you that over this period, Net IBRD financial flows increased significantly, which means lending to India increased during this period between 2017 - 2019. Make of this what you will, but one must wonder to what extent are the World Bank’s institutional incentives to grow its lending portfolio are at odds with its role as a development and knowledge partner of the world. If these priorities are currently misaligned, as indeed they seem to be, they need to be fixed urgently.